by David Walls-Kaufman

One of my favorites of my short stories. It has been rewritten several times and was originally published under the title Plight of the Locusts. It is based on a true event involving the Mexican drug cartels.

DAVID

“Remy, I am going to go over the Border.”

The 20-year old woman hefted their small boy. “What do you mean? When did you decide to start thinking like this again?”

Tippy ducked his head and shrugged.

“Bernardo and Felix are going.”

The couple stood near the open doorway of the family’s small house made of dirt brick and ancient repurposed windows and doors splintered from the sun. “Tippy, we have already talked about this!” The loud bray of locusts sounded outside. The sheen of white light was that of the desert.

Her husband could barely look at her.

“I think it is best to go with Felix and them.”

“What about me and Sancho?” She hiked the boy on her hip.

Tippy scrunched his head deeper between his small shoulders.

“They are going. I can go with them. It’s safer if we go together.”

“So, you are going to leave your boy and your wife?”

He put his hands in his back jean pockets.

“We talked about this. I’m not letting you go.” She hiked the boy again and rubbed an itch on her jaw on her shoulder.

“I can do more good for us up there.”

She nodded in frustration, conceding the obvious. “Okay. Okay. Your son will do better never seeing you up there?” She rocked the baby soothingly. She glared at her man like he too was a child. “Short term, Tippy. But what about the long term? Hmm? What about that?”

Tippy stared at the burnished dirt floor.

“I don’t need you to think short term, Tippy. I need a man who thinks long term. Hmm? Right? Do you understand me? I can’t do this alone.”

“We can all go up together.”

“With the baby? Really? Look at him. That’s what you want?” She waited for him. “I’m not going up there. This is our home. My parents need me. Your parents need you.”

Tippy’s mother came to the bright door, putting her hands on either jamb. The two-room house was sixty years old. The wood framing from before Pancho Villa. The lazy sounds of the locusts moved in and out of phase.

“What’s going on?”

“I want to go over the Border.”

The woman’s name is Marta. She looked inquiringly at Remy as if nothing was wrong with this, in the end. She shrugged. “Why not let him go?”

“I told him before, Nunu.” Remy shook her head.

“Dios mio,” Marta said.

The baby started to get upset. Remy rocked him.

“This is not the answer. We need our good men home.”

Marta raised her hand in solemn frustration and walked away. She halted three steps out in the sun then slowly turned back. She returned to the door and replaced her hands on the jambs.

“You two shouldn’t fight. It’s not good for your health.”

Remy shook her head. The boy looked tearfully at the adults, screwing his head this way and that as his mother cradled him.

“No. This is not the way. Long term.”

Marta looked at her son. She shrugged. Tippy kept his head hung and scratched once at the back of his neck. His pointed cowboy boots handed down from his uncle in this very room were white with dust from the bull ranch where he worked as a hand.

“He can make money.”

Remy shook her head.

Marta lifted her hands in surrender and made to leave again. This time, she simply turned around and replaced her hands on the jambs.

“He can send money home to us.”

“What do we need?”

“Aye. Shit.” Marta shook her head.

“Seriously. What do we need? What do we need that we won’t get one day if he stays and we all work?”

Marta said nothing.

“Running away from Mexico is not the answer. I want a better world for my son, here.” She kissed the boy. He is sensitive and doesn’t like adults fighting. “His father running away to America for a few dollars is not the answer for what’s wrong here that makes him run away.”

Marta turned to lean against the door. She crossed her sandals. “This is true.” Marta looked at the pale leaves of the mesquite trees in the ravine.

“What is there in America that you are chasing? What magic do they have that makes you think you need to chase what they have, Tippy? Eh? Tell me?”

“They have money. That is magical.”

“Okay. But why do they have that magic, eh?”

Tippy shuffled. He wanted to avoid fighting because he never wins.

“They have the money because they have it.”

“That’s not the reason, husband.”

Marta looked at a finger. She looked at her daughter-in-law.

“They have money because they have a stable country. They have a stable law.” Remy’s knees were tired and she sat on the bunk draped with blankets under the window that served as a couch. “They have courts that work. Police that work. Because they have people up there that insist on these things being done. That is why they have money.”

Marta shrugged noncommittally and looked away.

Tippy shifted his hands to his back pockets.

“We will never have those things if our good men run away from here, Tippy.” She bounced the boy. She could tell he would cry if she made him go down. “We have to bring what they have down here. Running away from this to go there and nibble will change nothing here.”

Tippy glanced up at her briefly.

She is always right. She is too smart for him.

That is the worst trouble for his being married to her. His friends know the situation. They give him a hard time. He accepts it because he knows it is good to be with a smart woman, and for the man to see it when it is true.

“I can go learn from them. Send money. Come back.”

Remy nods. “Okay. How many years? . . . What if something happens to Mama? Or Sancho? What if he dies? What if I die?”

“Caramba,” Tippy said, displeased she tempts fate.

“Caramba,” Marta said. “Girl. You go too far. That, should not be said.”

Tippy twisted his head, refusing to look at her again.

He would kill himself if such awful things should happen.

“And all those years away you could be here doing something. Like I told you before.”

Marta nods; Tippy nods.

“The FCN,” Tippy mutters.

“Exactly. Fighters. They have connections. You are a good worker. They know you. There is enough work here. And they are here.” Remy stopped bouncing the boy. She squared him up and looked keen into his large beautiful eyes and kissed him full, with a smack. She put him on the floor. He trotted to his grandma’s bare knees in her pink gingham shorts and leaned on them, looking out for the shrill locusts invisible in the pale green canopy of the mesquite descending into the white ravine.

Tippy rubbed the back of his neck.

“Maybe she is right, Titi?”

“What should I do?” he asked his wife.

“The FCN are Christians and only they are standing up to the criminals and protecting people. I told you. That is the way.”

Tippy nodded faintly. He turned and leaned his weight on the wall by the doorframe. His shirt is filthy with dust. He still looked down at his boots. They are the finest thing he owns.

“Let’s go talk to Señor Ramon,” Remy said. “He knows you.”

—-

The family of three walked up the hill on the road out of Apatzingan up to the larger house made of white-painted concrete with a two-car garage and a clean 2012 Ford F-150 parked in it. Two young men sit on the low stone wall in front with automatic rifles. An old truck approached with a hole in the muffler and Remy quickly reached for her son to guide him more to the shoulder of the road. Two men are in the truck. One held a rifle.

“Hola, Tippy,” called the driver in passing.

Tippy barely looked.

“Hola, Samuel,” Remy answered.

She looked at Tippy. The men are FCN.

Sturdy, fanciful grillwork covered the car port and all around the second story balcony, a bit like a fortress.

In the shadowy front room, they found Don Ramon. Three other young men were also in the house and the voices of at least two women can be heard in back. A child too. Piled on a table are four AR-15s and two Kalashnikovs, assorted pistols and ammunition boxes. One of the young men nods and says hello as he repairs one of the pistols. Don Ramon sits squarely beneath the ceiling fan in the middle of the room. His floral shirt is open and sometimes he fans himself with a straw cowboy hat. His head is unusually long and rectangular, his skin dark, his toothbrush mustache stark and plain.

“Hola. How are you? Sit down.”

The family sits. The boy, Sancho, watches the man fixing the pistol.

“Don Ramon,” Marta says, “Tippy is thinking of going up North.”

“Oh? Many do.”

“Remy wants him to stay with his family and work with you.”

The Don nods sagely at Remy.

“I want him to stay and make life better here so we can one day be more like the United States. Not run away from our problems.”

The Don frowns. “Who will ever be like the United States? Maybe China will one day be like the United States, or even better. But we can make life better here,” he indicates Sancho, “for our little ones. Much better than Mexico is now. Now, it’s bad. God willing, we can make it better.”

“God willing.”

“God willing.” Marta crosses herself.

“Tippy is hard working and honest and he wants to join you and the FCN to fight the drug lords and make an honest living. We are from the same town. We want to help,” Remy says. Sancho leans deep into the space between her thighs and stares at the big guns across on the table.

“We always have room for another good man. He works now at Don Ortega’s ranch. If he needs more work there is opportunity.”

“Thank you, Don Ramon,” Remy says.

“Let me hear from Tippy directly, now. I know how his women think and how they love him. How do you want to help the FCN?”

“I am nervous about the FCN, Don Ramon.”

“Oh? Why do you have reservations, my son?”

“I know you keep the money you steal from the kingpins.”

“Yes. This is true.”

“I don’t like it. And I know others worry about this and I know the Church Fathers also find fault with you doing this. Isn’t it crooked? And don’t you risk just taking their place?” Tippy looked directly at the Don, but he slouched low against the chair back.

“Ah, see? This is a big problem for many,” the Don admitted.

He fanned himself with the hat. He was tall, quiet.

“This is true, many people worry for this practice. And the Church Fathers too, for some, feel I should not do this practice. But the money from the Church and our own collections is insufficient for a small army. It is good for us to grow and pay our soldiers a little something. They are volunteers trying to save their country from murdering cutthroats, but where else should the money go but to them and to food, equipment and needed weapons? Look what the cartels have. We have to stand toe to toe with that? And where else should the money go? To the police? To the government? Should we burn it? To me? If this were the case and I was as corrupt as they and our police then I would deserve to die like them and be put in the desert in the same hole as they by our own men.” He crossed one thin leg over the other. “So, no. This is a fine practice. It is turning what is plainly sinful into a benefice for our state.” He watched Tippy square. “This is war. Only once we admitted to ourselves that this was war did we start to win and scare the cartels and the incompetent cops.” He looked at the backs of his fingernails. “Is our self-defense just? So is stealing their drug money. It is all the same virtuous business.”

He looked frankly at Remy now, the smart one.

“I think this is the truth of it,” she stated, looking at Tippy.

“They are killing us, Tippy. It’s only killing back. Enough to show them who is the righteous and who is going to be the boss.”

“We did not start it,” Marta said.

“No, no. We did not.”

The Don looked out at the land sloping from the rise.

The land was parched and rang with locusts.

“We and the Americans both have a war against godless cancer on our hands, Tippy. If you go North, you will be a knowing part of the problem. And you know it. In your heart. They are waking up to a problem of godless people doing their best to tip over that great country with disorder and hedonism. Look at the shit they teach their kids in school at earlier and earlier ages to train them to think of their own sexual desires first before being good people in a sound society.” He emphasized this with his long index finger. “Goodness is mocked in every one of their movies and TV shows. We see it here. It cannot be hidden. They who do it don’t want to hide it.” He paused. “Every one.” He gazed down the land again. “Showing sexual restraint. Not taking the property of your fellow man. Working hard. Up there, they are coming to war. Down here, we are already at war.”

“Good and evil,” Remy said.

Marta and Don Ramon nodded.

“I like sex as much as the next fellow. I am no prude. But sex is the least important of the social virtues we build on. The most important is mutually respecting our work and then what is the basis of reward and punishment in our society. First, you lay that foundation of the respect. Our cancer is that our people need to work harder to understand the importance of a larger social and legal organization and to be faithful to keeping it pure from criminals. We have a problem ignoring the near reward of making the quick dirty money that pushes away the far reward.” He twitched his mustache. He smiled. His smile was surprisingly immediate. “After we lay this foundation, then we can chase each other’s women.”

Tippy smiled. Marta and Remy laughed. Marta covered her mouth.

“Don Ramon! You are not the man of God I thought you were!”

“I joke. I am old enough that I need the women to chase me!” He snickered at them. “I am still a soldier of God, even though I have never read the Bible.”

“How can you never have read the Bible?”

“Well, when I was made to do it as a child. I should study it as a man.”

“You know in your heart what it says,” Marta said, squinting advisingly.

The Don nodded. He looked back at the man with the pistol.

“How goes it, Fidel?”

“Good, Don. Two more.”

Little Sancho scratched his head, watching the pistol. He put his head back against his mom and yawned. The Don smiled at the size of the mouth.

“So Tippy, you want to be a fighter?”

Tippy’s face didn’t know which way to move. But the Don’s speech had made up his mind.

“We are going out this week, if you want to join.”

Sancho said, “I want to join.” He stretched his arms and yawned again.

The Don and his mother chuckled.

Tippy knew better than to be amused by such a thing.

“We will show you the ropes of what we do. But each man must decide for himself what future does he want for himself and his family.”

“It’s a lot of fighting,” Tippy said.

The Don frowned. “Their fighting will never end. Again, my young friend, they are not the same. Because one barbarian after another rises to the top to savage those below. No one is easy with that. Our fighting is to wipe out the savages, who will not be peaceful, and then build the prosperity and peace on the other side of the hill where we respect one another.

“Not every man is a fighter, Tippy,” the Don said.

—-

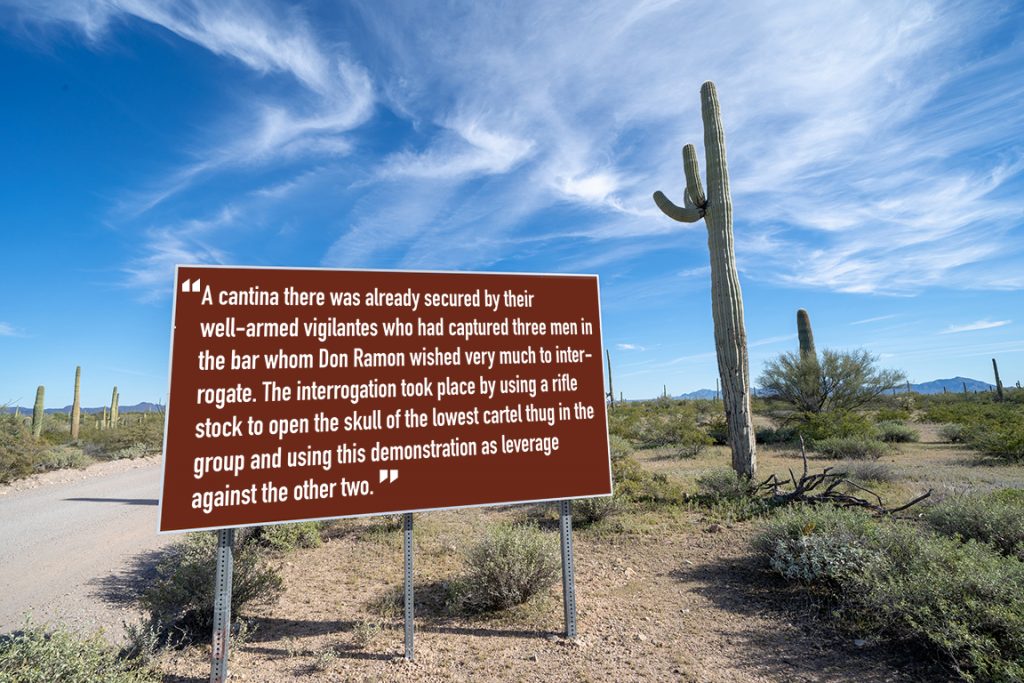

Tippy and the squad left Apatzingan in a big box van with three other large box vans each filled with a squad of vigilantes. At 9:30, they loaded out on the cobbled main street of a town on the outskirts of Uruapan. A cantina there was already secured by their well-armed vigilantes who had captured three men in the bar whom Don Ramon wished very much to interrogate. The interrogation took place by using a rifle stock to open the skull of the lowest cartel thug in the group and using this demonstration as leverage against the other two. It was known among the vigilantes that these cartel thugs knew of the whereabouts of some others. The Don used his cell phone to give the location to others of his men, and Tippy loaded back with the other vigilantes into the box vans.

The vans drove back and forth through narrow streets until the men got out again at a large old apartment building where the men they were looking for had already been caught and tied up hands and feet with sacks over their heads. The Don came into the apartment and ordered the sacks taken off the three men and then he had them dropped out of the window into the alley two floors below. Tippy and the other vigilantes returned downstairs to the alley where the three men were groggy but still aware of their surroundings.

“You know why we are here?” Don Ramon asked the men again.

He wanted them to swim back to reality before anything happened.

“We didn’t do anything,” one man whispered, rolling in pain.

“You have only a minute to get right with God and ask forgiveness.”

“You have the wrong guys,” the man tried again.

Blood bubbled out between this one’s nose and broken teeth.

“Oh, no. We have the right guys. You should see what we did to your amigos to get the truth out of them.” The Don nodded at Tippy and Tippy shouldered his AR-15 and brought out his machete that he had sharpened expertly yesterday just for this occasion. The blade shone with ragged file marks. “The farmer, our friend, Jalisco. You remember? What did you do? Eh? What did you do, young man? To his boys. Tell me. Tell me and make your peace with your God.”

“You have the wrong guys.”

Don Ramon dropped this one and picked up the head of the next guy by the hair and throat and shook him sharply.

“Very little time left, boys. Or you will go to God black with your deed. Tell the truth. You know as well as we what you did to those tiny boys.”

The young man in the Don’s grip looked up at him in double fear. Double fear for what was about to happen to him and what would happen to him in the afterlife. Tippy watched him blink heavily, his lips smooshed from the pressure of the Don and another fellow, Pico, choking him.

“We killed them.”

“Yes! You killed them. For what?”

“Because the farmer did not pay.”

“Pay what?”

“The money—”

“Oh! You wanted your protection extortion money from him? You rat bastards. Why did he not pay you?”

“He said he did not have the money.”

“Oh? Why is that?”

“I do not know.”

“Maybe because he was poor?”

“Yes.”

“So, then. What did you do, you boys?”

“We killed them. With rocks.”

“Excuse me? I did not hear you.”

“We killed them. On the rocks.”

“Oh, that’s right. Now, I remember: You killed his four young sons by tying them up feet and hands, like you are now, and then bashing their brains out on the rocks. While he watched. He and his wife. Is that what you did?” The Don shouted all of this out loud so that his voice echoed down the alley. He turned to Tippy, his face flush with coldness. “Chop them up.”

The Don and the vigilantes not holding the three punks stood back and watched without any sign of emotion.

Tippy slung his machete up and down and chopped at the joints of each man. The blade sunk deep enough to stick with each bite. He wept as he cut. It was an outpouring that he did not really understand. He had known Jalisco, and his wife, and the four young sons. Sancho had played with them. He had seen the little boys the next day battered purposelessly to pieces.

“That’s for Raphael . . . . That’s for Mario . . . . That’s for Emilio.”

Each time he swiped apart a limb, he said a name, like a mantra. The blade was very sharp and made like the joints were thick saplings.

Another fellow helped him a little bit.

Tippy went around and around through the boy’s names.

They left the clothed limbs and bodies in a loose red pile in the alley for the other cartel members to see what happened.

—-

On the drive back to Apatzingan it was late.

They got into the town and no one was on the street.

Tippy jumped down from the truck and hefted his gear and started the walk out to his house. He did not think about what he had done. He thought about the weight of his rifle and gear and the straight shape of his machete in the treated canvas sheath stiff on his hip. The machete he normally used to cut brush on the ranch with the great breeding bulls of Don Ortega’s family.

Remy was waiting up for him.

“I have some soup.”

Tippy sat at the table by the stove as Remy turned up the single burner under the dented, burn-stained pot.

“Is Sancho good?”

“Yes. He asked where you went.”

Tippy nodded.

Tippy stood. “I have to clean something. Is there water?”

Remy nodded at the bucket of water waiting for him by the back door. Tippy took a rag and his machete and the bucket and went out behind the house. The sky was full of stars. Remy inside opened the cabinet.

Tippy took a moment to listen to the sound of the crickets.