Book One: Wazku Vanishes

by David Walls-Kaufman

This was a short story submitted to Liberty Island and it was rejected because there wasn’t enough to it. I disagree. My vision of the story was to show a hopeless future where ordinary people had no chance. The LI editor suggested it became a larger story. At first I thought this was a dumb suggestion—then suddenly I imagined Robot Archangel and thought what a cool story it would be. The opening with Milton Aras was kept even though it was not part of the original short story.

DAVID

Your worst enemy was your own nervous system.

—-George Orwell, 1984

Milton Aras did not know how to respond.

How isn’t this Man’s Inhumanity to Man in the eyes of our God?

Aras revolted instinctively.

“Wait! Stop!” he yelled.

Rage crept into his voice. “You say our god? Aren’t you machina? You aren’t even alive! What’s this talk of any god being your god?”

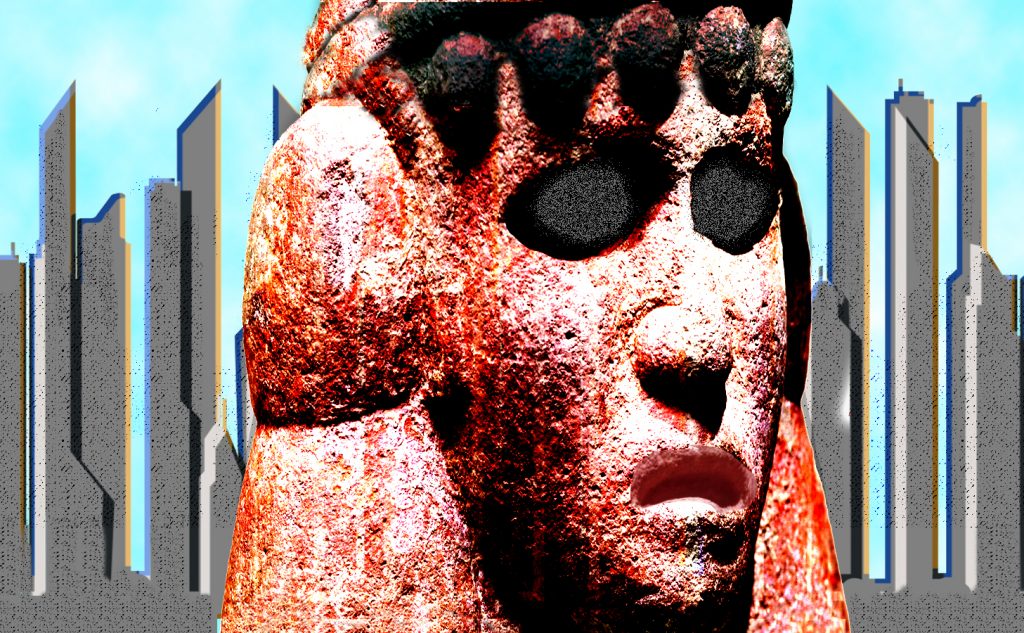

The orange-red Aztec skull blazed silently.

“You have no say in this! This is a fight between people!”

What do you do, Aras, when one bad animal torments others?

A hot pain burbled in Aras’s gut.

Say it, Aras, if we are so unkind!

A sound welled up. A whistling, shaking, tearing roar. It quaked out of the very bonds of space and time around them. Somehow Aras knew this was the sound of every prayer ever uttered since the moment the first man became more than a beast and believed there was a god that might be spoken to for relief from wrong. Aras heard the team shouting and ducking under desks and chairs behind.

But Aras knew all the technology in the world was no protection.

They were coming for him.

The sixty-year-old citizen stepped down from the dray cart into the rain and into the cold puddles in the empty road and felt the rain pellets drum across his hat and shoulders and fire off the canvas roof of the cart. The city sky had wept rust-smelling rain all day into evening. He walked up the broad stairs to the ornate bronze doors of the closed and dark government building, and turned. The cart driver snapped the reins, the lines sprinkled white rain drops in the streetlight. The brace of mules shook their long-eared heads and rattled the cart away over the cobbles into the dark.

The citizen waved thanks. He did, indeed, feel helped by the driver’s mantra of prayers. The driver had said what he thought of this odd nighttime appointment beyond First Gate, and prayed for him, many times. The driver had asked:

“Dost thou think thine art to see the one they call The Jolly Man?”

Did the driver speak in the old dialect because he was uncertain of Wazku’s fate? “I have never heard of a ‘Jolly Man’.”

“It is said He is the one thy dost not wish to see!”

“I have no trouble with the government.”

“Yes. But who ever does?”

“I am a simple pawner.”

“I am a simple driver of mules!”

They had been silent, again.

“Let me see again.” The driver examined the papers more carefully under the next arc light, leaning his broad hat away from the light, droplets pelleting paper.

“One cannot tell what trouble is or not,” the driver said again. He handed back the letter without looking at the citizen. “There is no trouble for you, citizen. And yet, I will pray for thee and thine family.”

The citizen entered the high gloom of the government building lobby. Under the grand geometric cornice sat a stocky guard with black hair at the reception cell. The citizen brought his damp-softened summons to the cell. The guard barely looked up. “Please?” said the citizen. The guard made no real sign of what the citizen should do.

The citizen crept past toward the huge bank of elevators.

“If thine stance with our officials was truly dour,” the driver had said, “then they would have come for you with The Robes.”

So, how bad could it be?

His finger trembled at the button. He glanced again at the office number. The 632nd floor. His chest hurt. His heart was very timid these years. The elevator whooshed down and compressed wind from the shaft pushed the dirty tails of his long coat. The grand bronze doors yawned. Inside, the citizen heard faint pleasant flute muzak. He had never before heard recorded music. Such delights!

The elevator closed and whooshed up, and up. He felt it in his heart, rushing up to Heaven, or God, if God existed over these places.

Ding. A gentle bell rang sweetly.

The citizen stepped into a low lit empty corridor that peeled off down an endless hall in both directions. Room number 632-146. A wall plaque pointed right for even-numbered, left for odd. His breathing hurt more.

He thought of his three-year old grandson, left with him and his wife after the death of their son after the poor lad was kicked to death by a horse.

He walked and walked. Finally, a door like the rest. He knocked. No answer. He swallowed; he had no spit. Did this mean he had fulfilled his obligation? No. Surely, they would come for him. In the way the driver had said. He tried the nob. It turned. He let go, startled. His heart ached like misery in his chest, but he walked in.

“Master Wazku?” a happy voice said from beyond an opaque screen. “Don’t stand on ceremony, dear sir. Enter, Master Wazku! Enter, by all means!”

Beyond, the most handsome space for bureaucrats! Dormant visuals hung over the desks unmanned at this late hour. The citizen had never seen such wonders and thought they were jewels hanging by invisible wires in the air. Behind the desk on the right sat a fleshy man in an old-fashioned business suit and tie before a huge window overlooking the lake and the most incredible vista of the Tall City beyond the First Gate. The citizen had never even imagined the Tall City from this perspective. It was petrifying to be walking around up so high. It was so beautiful he thought he might cry! He knew of no one with any relatives who worked for the government or who lived beyond the First Gate. He had heard stories, but he could not believe he was actually here. The fleshy man at the desk was youngish with jet black hair and a black beard that offset uncanny white teeth as he smiled and indicated a chair for the citizen. White the shade of those teeth existed nowhere in the citizen’s world, not even in porcelain kitchen tiles in buildings from the ancient times. “Please, for cheer, Mr. Wazku! Be unfeared. I have little bad to tell you.”

Again, the laughter, the hand, welcoming.

The citizen crept forward, unable to look from the view.

“Mr. Wazku. Why do you act like a man afraid?”

“I am not afraid. I have nothing to fear.”

He lied. The height was incredible. Would the building fall?

“Oh, but we all have something to fear. Yes? It is a part of life. Yes?”

“I am untroubled. I have done nothing wrong.”

“Of course you haven’t! You are a good man! This, we know! But, when you say it like that, so suredly, then I know you have done something.”

“I am a simple pawner.”

“There. You see? A money-lender! This is trouble for you, yes?”

The citizen shook his head stubbornly. “I am a simple pawner, and my wife runs a four-table coffee shop, Monsieur.”

The official’s smile changed to one of sharp comprehension. “I see in you a man who knows how to talk to a public official, oh, yes.”

“Oh, no, I do not. I never wanted the pleasure.”

“We are both men of God, and, oh, yes! You do know how!”

“But, I have never been called up in my life. I am never trouble. I am a simple pawner who helps other Sons of God with small money problems.”

“That is what your neighbors told you to say, yes?” The man grinned warmly, as if it was no problem; no big deal, everybody did it.

“No, no. I was embarrassed; I spoke to no one. No one coached me how to talk because I did not want to be shunned, and my family.”

The bureaucrat maybe did not believe him so much. “I think maybe you are lying to me. But—what does it matter? Who does not lie to the government, yes? Ha-ha.”

“I would not lie to the government. I do not want the trouble.” The citizen held his hands as if to presume to lean them on the front of the desk, then thought better of it, and folded his hands in his lap.

“Make yourself comfortable,” the official urged.

The citizen stayed where he was.

“Mr. Wazku, I am Alfred Wah, Official Sub-Altern at the Bureau of Theological & Civic Maintenance, at your service.” Manicured fingers politely touched his midriff. “And you are here in our Al Hariri Branch Office, First Gate.”

The citizen was not overly bright. He had accepted this of himself since his early schooling when he decided to favor wrestling over book study. “Do you want me to take a poll of some kind, if you read it to me? I am always quite satisfied!”

The official laughed louder. “Of course you are! You are a model citizen!”

“I am grateful you think so. No record is of me complaining.”

“Do you have any complaints at all, Mr. Wazku?”

“No. I do not believe I do.”

“How old are you, Mr. Wazku?”

“In my sixties.”

“Really? You look much older. You and I are close enough in age, actually. Look at me! I look much more vigorous! And you have no complaints with your whole life?”

“No. Not really, no.”

“How about with your wife?”

Was this it? His wife? Had she done something? He bumped his glasses up his nose. He was in queue for a watery eye operation, and had been for four years. His wife had been more angry about it than he, but she never dared say anything outside the shop. “No, I am unangry with my wife. She seems to be a good person.”

“’Seems’ to be, Mr. Wazku?” The smile, forgiving all.

The official turned in his chair and smiled out the window at the vast space of the dark lake and the cityscape across. The night was the color of char, and the lake the color of ashes, and the buildings that ringed it rising up to three and seven hundred stories, with more buildings beyond, unending.

“The truth is, Master Wazku, you are here not because of your conduct, but because of the conduct of your people five hundred years ago.” A visual leapt up, and he checked himself. “Yes, five hundred years ago.”

Wazku flinched in fear from the abrupt appearance of the visual. He knew not what it was. “My ancestors did something wrong a long time ago?”

“Yes. Sadly so.”

“What did they do?”

“He was a writer.”

The citizen said nothing.

“He wrote about political things. About the government.”

“What is ‘politi—?”

“Things to do with power and government.”

“About the government five hundred years ago?”

“Yes. But it does not matter. That was the beginning, you see? And he, your ancestor, was pointedly critical of everything, even the Religion of the State.”

“What did he say?”

The official shrugged. “He was uncomplimentary.” He pouted. He glanced up at the visual again, checking a detail. “Yep.” He frowned. He leaned back in his chair and joined his hands behind his head, twisting.

“That is all you have for me?” Wazku thought how ironic all of this was. He remembered the summons coming in the pink envelope, and his wife, Indira, holding it up for him to see, the fear and surprise registering only in her eyes. How they carried it to the neighborhood scribe to have it read. “He was ‘uncomplimentary’?”

The official pushed his mouth sideways. The Tech alerted him now to let him know that the citizen approached a Threat Level 3 from a Level 2. The official saw Wazku sense the danger and respond to bring his anger down.

“What has that to do with me, sir? It was so long ago.”

“Yes, but must we not deal with such things?”

“But,” the citizen sighed, “I never even heard about him. And even you do not know much about him.”

“His name was David Wazz-Koffu-man. He was a writer. Your name, you can see how it derived from him.” He sniffed. “You are his blood.”

The citizen put the fingertips of both his hands together to plead the absurdity of this blot against him. “How would I know? All I know is what you tell me.”

The Tech again alerted Mr. Wah to the Threat Level status change because Wazku not a minute before had hit a 2.68. Now he was at 2.2 headed to 2.4.

“He encouraged others to resist what now is.”

“And so, he wasn’t even successful?”

“It is needed for Rightness & Instruction.”

“Was he critical of The Religion? But my entire family have been faithfully of The Religion since our conversion long ago.”

“Four hundred years ago.”

“There. You see?”

“But there it is! Thou ist not Original, ist thou?”

The citizen smoothed his fingers over his lips like drawing them to a fine point. That was it. He had no answer.

The official said, “I just came back from vacation with my family. We went to Lake Mire-gan. Do you know it up there, Mr. Wazku? So lovely. So unspoiled. Buildings only thirty or forty stories tall around the lake, you know. My family always has a good time. I too have a boy.” The official leaned down onto his elbows as he gazed with some vague emotion of sympathy at his guest.

“Do you want to know what your sentence is?”

“I do not want to know.”

“See? You are a smart man; a brave man.”

“Given my crime, the penalty surely is equal to it.”

The official made a fingertip bell-tapping gesture. “See? You still have the defiance of the writer in you, so is it not the Will of God?” The official up-glimpsed to see that Wazku remained flatlined at Threat-Level 2. Not that it mattered. He was merely curious about the man’s psychology.

“What of my family?”

The official glanced up at the visual. “To be determined.”

“Can I say goodbye?”

“I’m sorry, not for this offense. They come for you now.”

“The Robes?”

The official nodded.

Wazku sighed. He could not believe this would be his fate after a life lived such as his. The Robes! “Will we be punished, together?”

“No. Not for this offense.”

“They had less to do with this than I!”

“People can be trusted to do stupid things if they do not periodically see another face the Portraiting.” The official raised up his thumbs and protruded his lips to make a faint popping bubble sound.

The citizen felt hot weeping crawl up his throat as he thought of his grandson.

“I know it is a sad thing with thine children.”

“You cannot imagine how absurd; how cruel.”

Wazku went up to a 3.

Again, the upraised thumbs.

“We are 25 billion, sir. It hardly makes a difference.”

“It does to him.”

A faint shrug. The gesture carried with it the extent of feeling by so many in this hard and strange world.

“Paradise is nigh, Master Wazku.”